Contents

Methodologicall Explanation

The study was conducted in the spring of 2024.

The purpose of the Study: To identify and describe the experiences of queer individuals related to encountering situations of violence and seeking help. The reseach aimed to uncover both general experiences with various forms of violence or manifestations of violence in partner and familial relationships, as well as such experiences that occurred during the past year, 2023.

As regards the forms of violence, the study touched upon the following:

- information violence — including informational pressure, distorted information, suppression of facts, and similar tactics;

- psychological violence — insults, threats, blackmail, control, manipulation, and any harm done to mental health;

- neglect — violation and non-fulfillment of agreements and duties, ignoring needs;

- physical violence — beatings, bodily harm, shoving, kicking, slapping, et cetera;

- sexual violence — coercion through force, threats, or deception into sexual activities in any form, including harassment, unwanted touching, and similar actions;

- economic violence — coercion based on material dependency;

- identity-based violence — including misgendering, threats of outing, et cetera;

reproductive violence — coercion into pregnancy, childbirth, or abortion; coercion into sex with someone for the purpose of conception, et cetera.

The target group comprised individuals aged 16 and older, identifying themselves as queer and residing in Russia in 2023.

To collect the data, a standardised self-report questionnaire was created in Google Forms. It contained questions related to the following areas of interest:

- socio-demographic characteristics of individuals,

- awareness of relationship violence,

- experience of violence by a partner or relatives (including types of violence),

- experience of perpetrating violence against a partner or relatives,

- seeking help in cases of violence.

A total of 1,239 individuals responded to the invitation to participate in the study. During the target group eligibility assessment phase, the following responses were removed from the database:

- 11 responses from individuals who did not reside in Russia in 2023;

- 36 responses from individuals who were under 16 years old at the time when the study was conducted.

In total, 1,192 responses were included in the data analysis (the final sample).

Mathematical Statistics Analysis of the data included the calculation of frequency distributions for all indicators.

To test the hypotheses that there are subgroups among individuals that experience relationship violence more than others (based on age, place of residence, sexual orientation and gender identity, as well as the level of openness), cross-tabulations of key indicators were calculated with statistical significance assessed using Pearson’s chi-squared test.

Socio-demographic Characteristics

The average age of individuals whose responses were included in the final data analysis was 25-26 years (with the modal age being 19 years), with a range from 16 to 58 years. The distribution by age groups was as follows: 27.1% were aged 16-19, 31.6% were aged 20-24, 10.2% were aged 30-34, and 13.8% were aged 35 and older (see Table 1.1).

More than a third of individuals (39.8%) lived in capitals (Moscow, Saint Petersburg), nearly a quarter (23.8%) resided in other large cities with over a million inhabitants, 14.1% lived in major cities with populations ranging from 500,000 to 1 million, 10.4% were in medium-sized cities with populations of 250,000 to 500,000, and 6.6% were in small cities with populations of 50,000 to 250,000 (see Table 1.6). Only a few lived in rural areas: 3.0% in settlements with populations of 10,000 to 50,000, and 2.2% in settlements with fewer than 10,000 inhabitants.

Just over half of the individuals identified as women (52.6%), 29.0% identified as men, and 18.4% identified as non-binary (see Table 1.2).

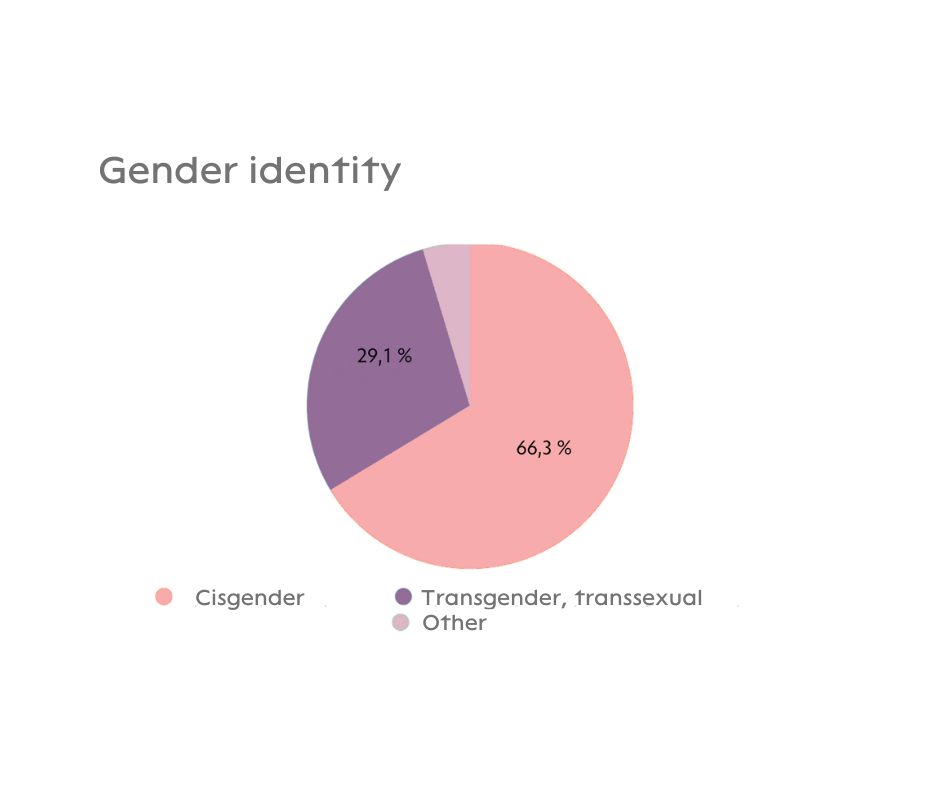

66.3% of the respondents identified as cisgender, 29.1% as transgender or transsexual , and 4.6% as other (see Table 1.3).

40.7% of those surveyed defined their sexual orientation as homosexual, 33.3% as bisexual, 6.9% as heterosexual, and 19.1% as other (see Table 1.4)

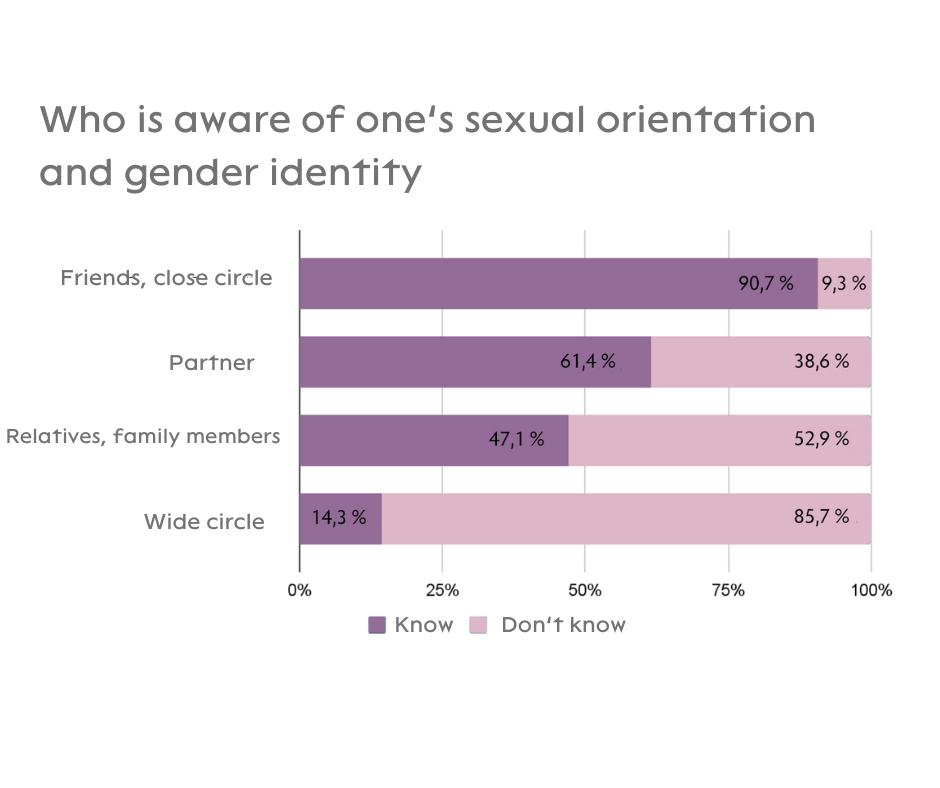

Only 3.4% of individuals indicated that no one knows about their sexual orientation and gender identity (see Table 1.5).

14.3% of individuals pointed out that everyone (a wide circle) knows about their sexual orientation and gender identity and that they do not hide it. The vast majority (90.7%) stated that they had informed their friends and close acquaintances about their sexual orientation and gender identity.

Around half of the individuals did not inform their relatives or family members about their sexual orientation and gender identity (52.9%), while approximately one-third of the individuals (38.6%) did not inform their partners.

Awareness of Relationship Violence

Two out of three people asserted that they are certain they know what constitutes healthy, non-violent relationships (76.4%), while 23.6% were unsure if they knew what such relationships were (see Table 2.1).

The impact of sexual orientation and gender identity on the awareness of what constitutes healthy, non-violent relationships was as follows:

- men — a ratio of 1:3; a statistically significant difference (x² < 0.05);

- cisgender people — a ratio of 1:3.7; a statistically significant difference (x² < 0.01);

- heterosexual people — a ratio of 1:5.3; a statistically significant difference (x² < 0.01).

Those who were certain about what constitutes healthy, non-violent relationships were almost twice as common among the residents of large and medium-sized cities (250,000–500,000 population), and slightly less common among the residents of capitals and other large cities with over a million inhabitants (a statistically significant difference, x² < 0.01) (see Table 1.6).

The least informed about what constitutes healthy, non-violent relationships were:

- non-binary individuals — a ratio of 1:2.4, a statistically significant difference (x² < 0.05);

- individuals with transgender or transsexual identities — a ratio of 1:2.4, a statistically significant difference (x² < 0.01);

- residents of rural areas — a ratio of 1:2.2–2.4, a statistically significant difference (x² < 0.01);

- individuals with non-binary sexual orientation — a ratio of 1:2.2, a statistically significant difference (x² < 0.01).

* Henceforth, the term refers to individuals who described their sexual orientation using terms other than «homosexual», «bisexual» or «heterosexual.»

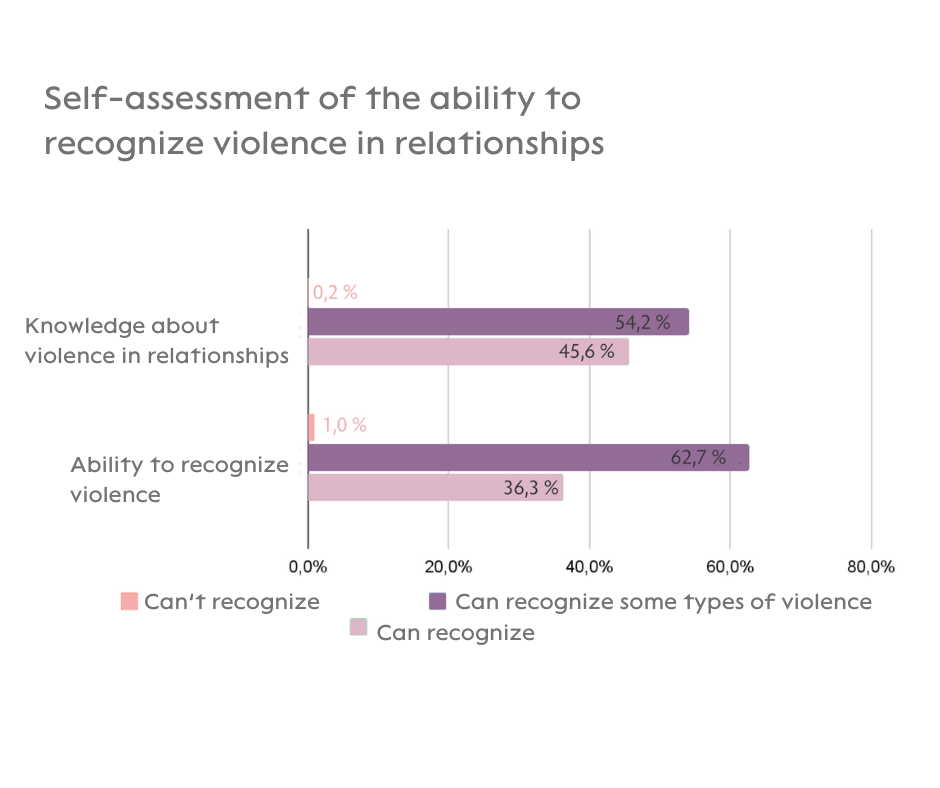

Just under half of the individuals (45.6%) stated that they know what relationship violence is, but only 36.3% were confident they could recognize it (see Tables 2.2 and 2.3). A slightly larger proportion (54.2%) specified that they were aware of some types of violence, and not aware of others. At the same time, 62.7% would be able to identify only certain types of violence.

Individuals with a homosexual orientation were more likely to be uncertain about what constitutes relationship violence — a ratio of 1:0.7, a statistically significant difference (x² < 0.05). Similarly, those with a non-binary sexual orientation also had a higher likelihood of experiencing doubt about what constitutes relationship violence — a ratio of 1:0.7, a statistically significant difference (x² < 0.05).

Overall, individuals distinguished between «more overt» violence, which they could recognize, and «more subtle» violence, which was more difficult to identify and the boundaries of which were perceived as more «blurred»:

- «It is most difficult to see the psychological violence for what it is, as sometimes you cannot tell apart care and overprotection from violence immediately.» (cisgender heterosexual male, 21 years old, resides in a large city).

- «Before anything else, I can see hints of violence in the way a person communicates with others. At the same time, it is not easy for me to see my partner manipulating me in situations that occur between us. Things like gaslighting, or minor restrictions which, in essence, restrict a part of me.» (cisgender pansexual woman, 19 years old, resides in a large city).

- «It seems to me that these days I am better at noticing violence showing itself, nevertheless, sometimes I am not very fast at reading certain forms of emotional violence and manipulation. I realise that they occurred only after some time.» (cisgender pansexual woman, 24 years old, resides in a capital city).

- «Noticing physical and sexual violence in the relationships of other people might be harder as the victims often try to hide it. Economic violence is easier to see. Emotional (shouting, insults, belittling the partner’s qualities, ignoring) is usually much more visible. In your own relationships, however, physical violence is the most obvious, while economic and sexual less so, with emotional being the least noticeable.» (non-binary transgender or transsexual person, 25 years old, homosexual orientation, resides in a large city).

«Physical violence is easy to recognise. When it comes to psychological violence, though, it is at times unclear where the line between violence and “just imagining it” is. Financial violence is also a complicated thing: say, one of the partners lost their job, and the other partner is not helping in any way during the ensuing job search. On the one hand, it’s not a big deal, but, on the other hand…» (transsexual transgender man, 20 years old, bisexual orientation, resides in a capital city).

0.2% of individuals responded that they do not know what relationship violence is, and 1.0% stated that they cannot recognize relationship violence. Among these individuals were (x² < 0.01):

- individuals with a homosexual orientation,

- individuals with a bisexual orientation,

- individuals with a non-binary sexual orientation.

Experience of Violence by a Partner or Relatives

The majority of individuals (83.5%) have experienced violence from a partner or relative at some point (see Table 3.1). 16.5% of individuals claimed that they have never encountered violence.

At the same time, the experience of encountering violence varied significantly based on sexual orientation and gender identity.

Individuals who identified as men encountered violence from a partner or relative less frequently (a ratio of 1:3.9; a statistically significant difference, x² < 0.01). Cisgender individuals also faced violence less often (a ratio of 1:4.1; a statistically significant difference, x² < 0.001).

Individuals who identified as women encountered violence from a partner or relative more frequently (a ratio of 1:5; a statistically significant difference, x² < 0.01). In particular, the experiences of violence were noted among (ranged by frequency):

- individuals aged 35 and older — a ratio of 1:9.9; a statistically significant difference (² < 0.01);

- non-binary individuals — a ratio of 1:8.5; a statistically significant difference (x² < 0.01);

- transgender and transsexual individuals — a ratio of 1:8.1; a statistically significant difference (x² < 0.001);

- individuals whose gender identity does not match their sex assigned at birth — a ratio of 1:8.1; a statistically significant difference (x² < 0.001);

- individuals aged 25–29 — a ratio of 1:7.2; a statistically significant difference (x² < 0.01).

Individuals who did not disclose their sexual orientation and gender identity to anyone experienced violence from partners or relatives approximately two times less frequently than others, both overall (a statistically significant difference, x² < 0.01) and in 2023 (a statistically significant difference, x² < 0.05).

55.3% of individuals have encountered partner violence at some point in their lives, compared to 44.0% in 2023 (see Table 3.2). In 2023, such violence was more frequently reported by individuals aged 35 and older (a ratio of 1:1.2; a statistically significant difference, x²<0.05).

Among those who experienced partner violence in 2023, the following types were reported (see Table 3.3, ranked by the number of mentions, multiple choice allowed):

- psychological violence — 75,8 %;

- neglect — 64,0 %;

- information violence — 56,6 %;

- sexualized violence — 28.0% (3.5 times more frequent than from relatives);

- physical violence — 25,5 %;

- economic violence — 22,3 %;

- identity-related violence — 17,9 %;

- reproductive violence — 4,0 %.

A few quotes illustrating situations of partner violence:

- «It wasn’t just distorted information, no. It was some kind of pathological lying, completely baseless, even about small details, and for unclear reasons. The distortion of events I had been present at, and portraying me as crazy because I remembered things differently. Shouting and temper tantrums…» (cisgender woman, homosexual orientation, 39 years old, resides in a city with a population of one million or more).

- «He kept saying: “I can’t wait for you to move in with me and give birth to our children. We all will be living together as one family” And I said to him: “ Did you even ask me if I wanted to move in with you and have children?” To which he said: “There is such a thing as the body clock. Right now, you simply don’t understand what you want. Just wait, you will come to me yourself after some time, and ask me to have a baby with you…”» (cisgender woman, bisexual orientation, 37 years old, resides in a major city).

- «I suppose sexual violence did occur. It’s not like my girlthriend raped me or put pressure on me because of my refusal. She just complained that she wasn’t getting enough sex and was feeling bad because of that. This led to me feeling some kind of guilt, and next time when she hinted at sex, I agreed despite not wanting it, I thought that I wouldn’t be worse for it, and she clearly needed it. My libido declined dramatically at that time. I had a need for masturbation, however, I almost never desired to have sex.» (cisgender woman, homosexual orientation, 20 years old, resides in a mid-sized city).

- «About one year into our relationship my partner suddenly came out as polyamorous. I myself am a totally monogamous person. Because of the pressure and emotional manipulation from my partner I was afraid of being left alone, offending him or making him mad. I didn’t want him to lose it on me or start threatening me with a breakup or self-harm. All of that forced me to accept his new ‘self’. We set the boundaries, which he happily agreed to. He swore up and down that he will never love anyone else like he loves me. Well, it turned out that it was nothing but lies: he didn’t keep his promise and was having an affair with another guy, at the same time not letting me go, playing with my feelings like they were toys.» (transgender/transsexual man, homosexual orientation, 19 years old, resides in a major city).

74.4% of individuals have encountered violence from a relative at some point, compared to 65.0% in 2023 (see Table 3.4).

Sexual orientation and gender identity significantly influenced the experience of violence from relatives in 2023.

Individuals who identified as male (a ratio of 1:1.9; a statistically significant difference, x²<0.01) and cisgender (a ratio of 1:1.5; a statistically significant difference, x²<0.001) were less likely to experience such violence.

Those who experienced such violence more frequently include (ranked by frequency):

- women — a ratio of 1:2.9; a statistically significant difference (x²<0.001);

- non-binary individuals — a ratio of 1:2.9; a statistically significant difference (x²<0.01);

- individuals whose gender identity does not match their sex assigned at birth — a ratio of 1:2.9; a statistically significant difference (x²<0.001);

- transgender and transsexual individuals — a ratio of 1:2.8; a statistically significant difference (x²<0.001);

- younger individuals aged 16–19 years (a ratio of 1:2.5) and 20–24 years (a ratio of 1:2.1) — a statistically significant difference (x²<0.001);

- individuals with non-binary sexual orientation — a ratio of 1:2.1; a statistically significant difference (x²<0.05);

- individuals with homosexual and bisexual orientation — a ratio of 1:1.9; a statistically significant difference (x²<0.05).

Those who experienced violence from relatives in 2023 reported the following types (see Table 3.5; ranked by the number of mentions, multiple choice allowed):

- psychological violence — 85.7%;

- neglect — 56.1%;

- information violence — 48.9%;

- economic violence — 47.1% (2.1 times more frequent than from a partner);

- physical violence — 39.5% (1.5 times more frequent than from a partner);

- identity-related violence — 33.4% (1.8 times more frequent than from a partner);

- sexualized violence — 8.0%;

- reproductive violence — 6.7% (1.7 times more frequent than from a partner).

Many instances of violence from relatives were primarily associated with childhood and adolescence, and the consequences of those experiences are often felt by the respondents up to and including today.

- «Threats to get rid of or kill my pet» (non-binary transgender, transsexual individual, bisexual orientation, 22 years old, resides in a city with a population of one million or more).

- «Gaslighting, saying that the memories I have of cruelty experienced in my childhood are made up.» (non-binary transgender, transsexual individual, bisexual orientation, 19 years old, resides in a large city.).

- «Sexual abuse by my stepfather when I was 10 or 12. The lack of opportunity to take a bath alone up until the age of 8-10. The ban on changing clothes in a separate room.» (non-binary transgender, transsexual individual, 16 years old, resides in a small town).

- «My dad used to beat me up severely when I was a child. And then he went to prison. After that my mom beat me up and made me stand in the corner of the room facing the wall for hours as a punishment for my kleptomania and the loss of interest in studying. She also manipulated me by saying I was the reason she became an alcoholic, she said that when I was little, I asked her to go to the store all the time, to buy something tasty, and to her it was the excuse to buy booze.» (cisgender man, homosexual orientation, 30 years old, resides in a large city).

- «In 4th grade at school a teacher sexually harassed me and several other girls. We didn’t really understand what was happening (he was fired without any scandal). My mom said that I only had myself to blame for not telling her about it at the time it was happening, so there was no reason to complain then.» (cisgender woman, homosexual orientation, 25 years old, resides in a city with a population of one million or more).

A significant portion of examples related to still occurring violence by relatives was connected with sexual orientation and gender identity of those surveyed.

- «Gossip, discussions of my sexual orientation, the breach of anonymity… I was banned from seeing my nieces and nephews because of my orientation.» (cisgender woman, homosexual orientation, 34 years old, resides in a medium-sized city).

- «Very often they tried to find male partners for me, and asked me to message them, so I would have heterosexual relationships, which, by the way, do not interest me at all. They also repeatedly asked me to have a baby soon, assuring me that the whole family will be taking care of the baby so I could be free to party and study. A disregard for my sexual orientation and constant conversations that pressured me and pushed me towards the males.» (non-binary woman, homosexual orientation, 20 years old, resides in a medium-sized city).

- «Even though they don’t know about my sexual orientation and the fact that my gender identity does not match the sex assigned at birth that wasn’t assigned at birth, my folks constantly speak terribly about LGBT people, saying that it’s fair to belittle and humiliate someone like me.» (non-binary person, bisexual orientation, 16 years old, resides in a medium-sized city).

- «Humiliation based on my sexual orientation, attempts to swing me round to having a “normal” orientation.» (non-binary person, homosexual orientation, 19 years old, resides in a capital city).

However, the examples touch upon more than sexual orientation and gender relations:

- «Rudeness, ignoring, threats to stop talking with me. It’s also unpleasant when they ask me to shut up when I raise unpleasant topics like war, for example.» (cisgender woman, homosexual orientation, 39 years old, resides in a large city).

- «Creating a negative and aggressive news environment. When the aggression is not directed at me personally, but I still suffer from the words. For example: “Who are these candidates, Western agents?”, “They are all traitors to the Motherland.” “We should’ve blown those ukrops* up ages ago.» (cisgender woman, bisexual orientation, 22 years old, resides in a capital city). [*’ukrop’ is a slur for Ukranians]

- «Manipulation by guilt, by family relationships, blaming me for being offended or saying something like “You’ve changed so much, and this change is for the worse” when I tried to assert my boundaries. Statements about how I should live my life, and how they don’t like my lifestyle and what I do. Non-verbal displays of negative attitude.» (cisgender woman, homosexual orientation, 32 years old, resides in a capital city).

Experience of Perpetrating Violence Against a Partner or Relatives

Among those who participated in the study, 54.4% had perpetrated violence towards a partner or a relative/relatives at some point in their lives (Table 4.1).

Notably, individuals from the youngest age group of 16-19 years reported this experience significantly less often compared to others (a ratio of 1:0.7; a statistically significant difference (x² < 0.001). Additionally, those who had not disclosed their sexual orientation and gender identity to anyone also showed a statistically significant difference (x² < 0.05).

Significantly more frequently, experiences of violence were reported by individuals aged 25-29 years (a ratio of 1:1.7) and those aged 35 and older (a ratio of 1:1.7), with the differences being statistically significant (x² < 0.001).

The types of violence reported were as follows (Table 4.2, ranked by the number of mentions, multiple choice allowed):

- psychological violence — 72.1%

- neglect — 39.8%

- physical violence — 36.2%

- informational violence — 34.1%

- sexual violence — 9.1%

- economic violence — 7.4%

- identity-related violence — 2.2%

Reproductive violence towards a partner or relatives was not mentioned at all.

Here are several quotes illustrating the perpetration of violence by individuals towards their partners:

- «Once I was in a relationship with someone I didn’t love. It was making me angry, so I took it out on him by yelling and cursing at him when he needed my support.» (cisgender homosexual man, 33 years old, resides in a rural area).

- «I was irritated by where the relationship was going, by the lack of attention and connection. It was making me angry and I wanted to share part of my pain, show it to my partner. That definitely caused tangible pain, I could have done it differently.» (non-binary transgender, transsexual person, 25 years old, resides in a large city).

- «In the last month of our relationship I made an account under a different name and would message my partner things like “You need to take the cat to the vet” or “Do a medical check-up”. It was neutral enough, but at the same time anxiety-inducing. What’s most surprising is that he didn’t even come to discuss the situation with me. He talked about it with friends, but not with me. Finally, when I told him that it was me and we’re breaking up, he got really mad and said that I ruined his mental health.» (non-binary transgender, transsexual person, 31 years old, resides in the capital city).

- «I used to send unwanted photographs of a somewhat explicit nature to the person who I liked romantically but who wasn’t reciprocating my feelings. I also sent unwanted and unsolicited gifts, and almost threatened to out them if my demands were not met.» (non-binary transsexual, transgender person, 19 years old, resides in a large city).

Quotes about the perpetration of violence by individuals towards relatives illustrate both relatively ‘traditional’ situations and those directly related to sexual orientation and gender identity:

- «At times, during her illness, my relationship with my elderly mom was difficult. I took care of her, a bedridden person, for almost 5 years, and at times I just couldn’t handle the situation psychologically. I would have emotional breakdowns.» (cisgender woman, homosexual orientation, 41 years old, resides in a city with a population of one million or more).

- «My children not putting away their toys caused outbursts of anger. I displayed anger and violence. Made them clean up. Manipulated them by threatening to collect and throw everything away. All those outbursts of anger happened after I experienced physical and emotional abuse in my marriage.» (cisgender woman, homosexual orientation, 44 years old, resides in the capital city.).

- «I was hiding my transition from relatives. I don’t know if that can be counted as violence. Generally, I regularly hide various facts about my life from them, like my plans to relocate to a different country, which I had been hiding for a long time. Considering that all of it caused suffering to my parents, I think we can call that violence.» (transgender, transsexual man, 35 years old, resides in the capital city).

Seeking Help in Cases of Violence

In the most recent case of violence that occurred in 2023, only 43.6% of the surveyed individuals sought help (see Table 5.1). Significantly more often, this was done by individuals from the youngest age group of 16–19 years (a ratio of 1:1; a statistically significant difference, x²<0.01)

The overwhelming majority of individuals sought help from friends and acquaintances (91.4%; see Table 5.2), while fewer approached a private specialist (39.8%). Consequently, the support received was primarily emotional and moral (97.7%), and less frequently involved professional psychological services from a private provider (40.1%; see Table 5.3).

Only in very few cases were there inquiries to organizations that assist queer individuals (6.6%), provide support to victims of violence (2.0%), or to the ‘Overcoming Together’ project (2.0%; see Table 5.2). Consequently, legal assistance was rare (2.3%) and emergency safety support was infrequent (7.9%; see Table 5.3).

More than half of the individuals noted that after seeking help, some aspects improved while others did not (61.7%), a third reported that things improved (33.0%), and some said that there was no improvement (5.3%; see Table 5.4)

In less than half of the cases the assistance received helped resolve the situation of violence (41.9%), while in the remaining cases it did not help (58.1%; see Table 5.5)

** It is highly likely that the term ‘private provider’ referred specifically to a female provider.

Overall, among the surveyed individuals there is a strong conviction that a complete break-up is necessary to stop the violence:

- «In the last case, the violence stopped because my ex-partner started a terrible divorce, with threats and home security breaches. From within the relationship, I did not see any violence and did not seek help.» (transgender, transsexual woman, bisexual orientation, 39 years old, resides in the capital city).

- «No amount of help or support will make a difference until something clicks in your mind and tells you to end this relationship.» (cisgender woman, bisexual orientation, 29 years old, resides in the capital city).

- «To end the family violence (mainly by older relatives) you have to go no contact with them. This is not something that we can afford…» (non-binary transgender, transsexual person, bisexual orientation, 24 years old, resides in a large city).

In some cases, the lack of timely assistance and support was highlighted:

- «I wasn’t given enough timely support. One queer support organization responded to me after a month, by which time I had already ended the relationship with the person who had been violent. The first session with the psychotherapist was scheduled for another month later…» (non-binary transgender, transsexual person, homosexual orientation, 23 years old, resides in the capital region).

Reasons for not seeking help were as follows (see Table 5.6, ranked by the number of mentions, multiple choices allowed):

- thought they could handle it themselves — 58.6%;

- did not consider the situation serious enough — 51.2%;

- did not believe anyone could help — 36.1%;

- did not know where to turn — 22.9%;

- did not feel safe, feared the situation might worsen — 22.2%;

- lacked financial resources to seek help — 20.6%;

- felt shame or feared judgment — 19.2%;

- lacked the psychological resources or strength to seek help — 17.1%;

- did not recognize the situation as violence — 16.7%.

Among those who had ever perpetrated violence against a partner or relatives, only a third sought help (33.3%; see Table 5.7).

Conclusion

The results represent the situation with family and partner violence among queer individuals aged 16 and older who reside in Russia.

Overall, partner and domestic violence is widespread among queer individuals — over 80% have experienced violence at some point. Almost all of them have faced violence from relatives (around 75%), and more than half (about 55%) have experienced violence from a partner.

The level of violence against queer individuals by relatives is approximately one and a half times higher than that by partners, both overall and for the year 2023.

Differences in the forms of partner and family violence encountered by individuals are also observed. For instance, violence from a partner is more often psychological, informational, sexual, and includes neglect.

In contrast, the forms of violence encountered by individuals from relatives are more diverse. These include psychological, informational, economic, and physical violence, as well as neglect and identity-based violence.

More than half of the individuals (about 55%) have themselves perpetrated violence against a partner or relatives at some point. The most common forms were psychological violence (twice as common as other forms), followed by neglect, physical violence, and informational violence.

It is important to note that aspects of sexual orientation and gender identity influence the characteristics of encounters with violence.

To illustrate, on one side are individuals who identify as men and/or cisgender and/or heterosexual. Among these subgroups, there is a significantly higher number of those who are informed about healthy, violence-free relationships, as well as those who encounter less violence in relationships overall and from relatives in particular.

On the other side are non-binary individuals and/or those with transgender or transsexual identities and/or non-binary sexual orientations and/or those whose gender identity does not match their sex assigned at birth, as well as those living in rural areas. They experienced violence significantly more frequently.

Subgroups with higher prevalence of violence also include individuals who identify as women, as well as those over 35 years old (particularly in cases of violence from a partner). In contrast, younger individuals (16-24 years old) more frequently experience violence from relatives. Not disclosing one’s sexual orientation and gender identity does indeed ‘help’ to avoid family and partner violence. Such individuals both experience violence less often and perpetrate it less frequently.

Less than half (about 43%) of individuals sought help in the most recent situation of violence in 2023. Notably, a higher proportion of those seeking help were from the youngest age group, 16-19 years old.

The overwhelming majority of individuals (over 90%) sought help from friends and acquaintances, primarily receiving emotional and moral support. Much fewer (around 40%) approached private specialists and received psychological services.

Seeking help from specialized organizations (for queer individuals, for victims of violence), as well as receiving other types of assistance (legal, emergency), are rare.

Reasons for not seeking help were related both to overestimating one’s ability to confront violence (‘Thought we could handle it ourselves,’ ‘Did not consider the situation to be serious enough’) and misconceptions (‘Did not believe anyone could help’), as well as low awareness (‘Did not know where to turn’) and fears (‘Did not feel safe,’ ‘Feared the situation might worsen’)

Clearly, these reasons can be used in campaigns aimed at raising awareness among queer individuals about family and partner violence.